By Jahn Olsen at Bloomberg NEF

The European Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) is the largest carbon market in the world. It was set up to be a cornerstone of EU climate policy, but it is hard to argue that it lived up to its remit. Oversupply and an inflexible design has meant the market delivered far lower prices than necessary to push coal out of the generation mix. That could be about to change. The EU recently completed a reform aimed at bringing scarcity to the market by strengthening the Market Stability Reserve (which went live in January 2019), and by adding other supply curbing measures in the market’s design in 2021-30. Governments in coal-dependent nations such as Poland and Romania are already calling for the EU to intervene to cool the market

Why carbon pricing matters – fuel-switching

Cap-and-trade markets like the EU ETS set a limit on the total amount of greenhouse gases participating installations can emit. Each emissions allowance (EUA) gives the holder the right to emit one metric ton of CO2, or the equivalent in N2O or PFCs. The number of allowances decreases linearly by 1.74% of 2010 emissions annually, which widens to 2.2% in 2021. Companies have to surrender allowances for their emissions and can trade to ensure they have enough to cover their emissions. It is trading that makes carbon markets efficient as it allows the market to reduce emissions in the cheapest possible way.

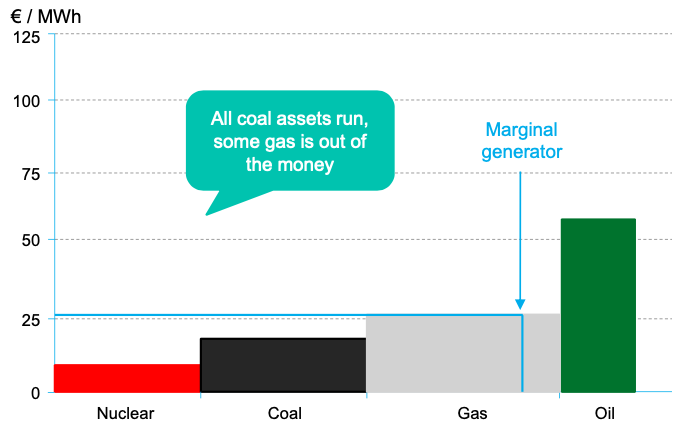

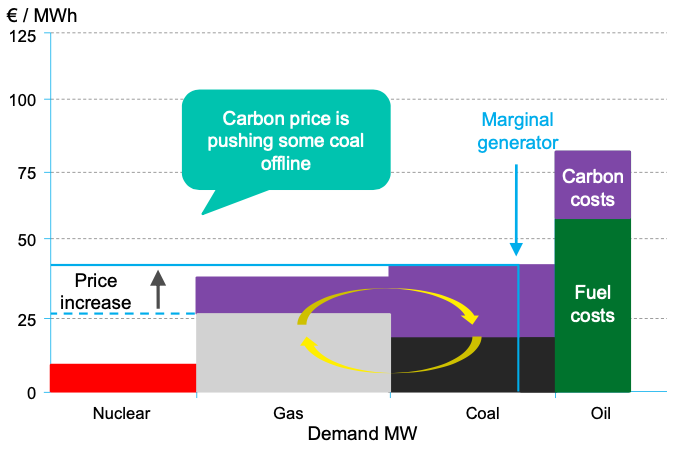

Figure 1. Illustrative merit order without carbon price (Source: BloombergNEF)

Figure 2. Illustrative merit order with carbon price (Source: BloombergNEF)

It is generally cheaper to produce power from coal than from natural gas. This puts coal plants in front of gas plants in the so-called ‘merit order’ in markets without carbon pricing. The flipside is that they are also more polluting, emitting roughly twice as much CO2 per megawatt-hour compared to gas plants. With a high enough carbon price, gas will move ahead of coal in the merit order in a process called ‘coal-to-gas fuel-switching, reducing emissions.

Economic downturn and oversupply

Fuel-switching is the cheapest form of abatement in the EU ETS. But the market has been oversupplied since its 2008 restart, which has led to a negligible carbon price. The U.K. implemented a carbon price floor as a top-up to the EU ETS price, which contributed to the decline of coal in its power market, but the EUA price has not been high enough to have a similar impact in continental Europe.

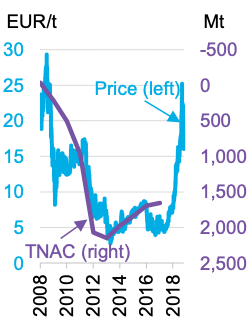

Figure 4. European carbon price and inverse total number of allowances in circulation (Source: ICE, BloombergNEF)

There has been a strong inverse correlation between the cumulative oversupply, or total number of allowances in circulation (TNAC), and the price of carbon, since the financial crisis. This relationship somewhat broke down in 2018 as the price of carbon has gone up despite continued oversupply. The reason for the recovery is that a large number of speculators have entered the market on the expectation there will be scarcity in the future.

The market’s oversupply is due to its inflexible design. The cap was calculated using verified emissions in the first trading phase (2005-07). The 2008-09 financial crisis led to a drop in economic activity and its associated emissions in Europe, however, and there was no measure in place to reduce supply in case of an unexpected drop in emissions. In the past few years, the EU has attempted to address the oversupply through multiple reforms, and supporters of a strong carbon market finally have a reason to be more optimistic.

The market stability reserve

In early 2018, the EU completed a carbon market reform, changing the future framework of the EU ETS. The reform is seen as quite ambitious, and the market responded by pushing the price to levels not seen since 2008. The biggest reason for optimism is that member state auction supply is being curbed by the market stability reserve (MSR), which started operating in January 2019.

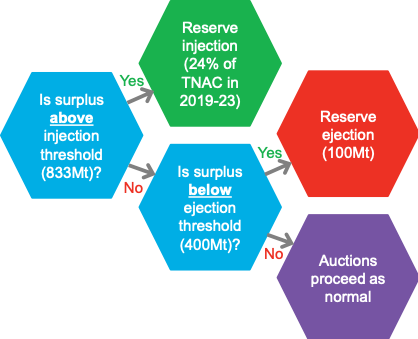

The MSR will remove allowances from auctions if the TNAC is above 833Mt and reintroduce them to auction if it falls below 400Mt, finally bringing flexibility to the supply of carbon allowances. The reform has doubled the MSR intake rate to 24% from 12% of the TNAC in the first five years (2019-23) of its operation. The change means that the mechanism will be able to quickly balance the market, bring scarcity to the market and push emissions reductions in the power sector.

Figure 5. Market stability reserve flowchart (Source: BloombergNEF)

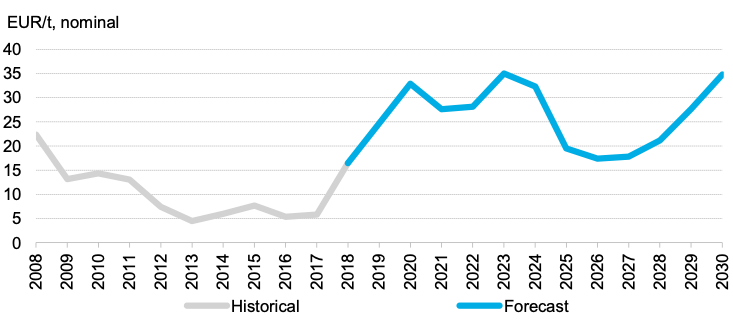

The MSR will remove 1,117Mt EUAs from auctions in the first three years of its operation alone, according to BNEF modelling. The market will be short on an annual basis from the year it becomes operational, quickly eroding the oversupply that has built up. This should push the European carbon price above 30 euros per metric ton by 2020 and keep it between 28 and 35 euros in the following four years.

Figure 6. Historical and forecast EUA price (Source: BloombergNEF)

Gas generators will probably benefit from the high carbon price in the early 2020s. We estimate that new build renewables will become competitive with existing gas from 2022-23, and cheaper from 2024 onwards. As a result, wind and solar should be built on the back of a high carbon price in the mid-2020s, permanently reducing emissions in the power sector.

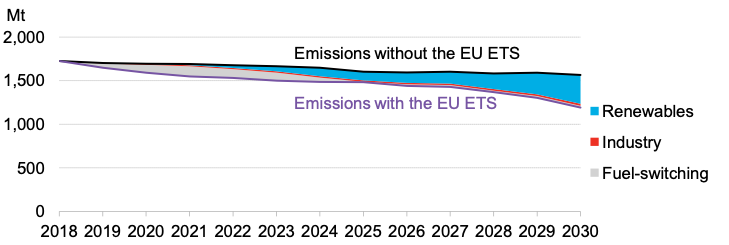

Figure 7. Forecasted EU ETS impact on emissions (Source: BloombergNEF)

It could be the time for the EU ETS to shine, if it is left to run its course under the current legislative framework. The difference in emissions between the no-ETS case and the ETS case above is 374Mt, around 350Mt of which is from the power sector – a 57% reduction in power sector emissions. That amounts to around 340TWh, equal to annual power generation on the Iberian Peninsula, if the replaced generation is a mix of lignite and coal (Assumes zero emission renewables replacing generation with an emissions intensity of 1,025g/kWh).

Coals downward trajectory in Europe

The writing is on the wall for coal in Europe, but it is not altogether clear if it will be the EU ETS or other policies that will have the largest impact on its demise.

The effectiveness of the EU ETS is vulnerable to overlapping policies and the market could drift back into irrelevance if large coal-dependent countries like Germany and Poland decide to completely phase out coal from their generation mix without reducing EUA supply equal to or greater than the resulting emissions reductions. A failure to adjust the supply of EUAs would lead to a lower price, and less EU ETS-driven abatement. In such a case, the EU ETS would act as a backstop to emissions rather than the primary driver of emissions reductions.

The good news is that EU member states are considering taking appropriate action to minimise the impact of overlapping policies. Germany, for example, is discussing the cancellation of EUA auction volumes equal to the emissions of the phased out coal plants. In fact, overlapping policies could make the carbon market even more ambitious. The German government, for example, has indicated that it will likely cancel gross emissions, rather than the net difference between coal and gas which will make the market shorter during the cancellation years.

Perhaps the biggest threat to the EU ETS is pressure from coal-dependent EU member states and emissions-intensive industries. The EU has shown that it is not afraid to tinker with the carbon market if it deems that it is not performing as it would like it to. There’s a risk that the European Commission could initiate a reform to weaken the MSR or add more supply if the EUA price goes too high, too fast. Coal dependent countries will claim carbon costs are too detrimental to their competitiveness, and industries will point out that there is a risk of carbon leakage (Carbon leakage in this context means European industry relocating elsewhere due to high carbon prices in Europe).

The European carbon market could be on the verge of becoming the cornerstone climate policy it was meant to be for participating countries. That might or might not include the U.K. as a direct participant, depending on the outcome of Brexit negotiations. The British government’s preferred solution is to design a nationwide ETS linked to the EU ETS, and it has pledged to implement a solution ‘at least as ambitious’ as the European carbon market. Looking ahead, the success of UK carbon pricing policy in accelerating the retirement of coal plants is a good indicator of the potential impact that the newly rebooted EU ETS can have going forward.