By David Kang at Bloomberg NEF

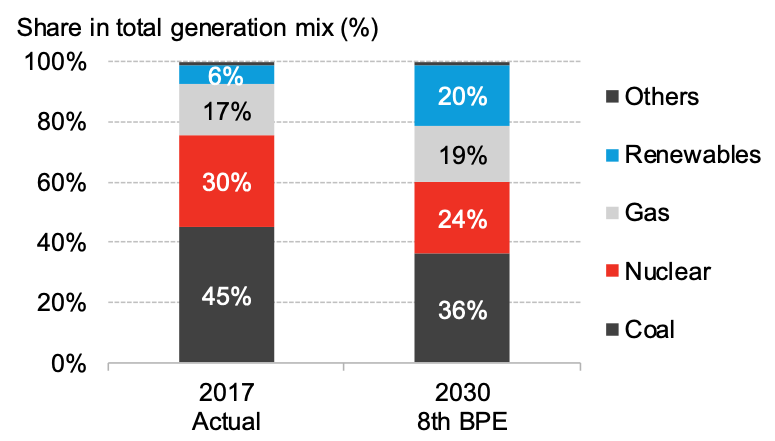

Coal generation has long served as a crucial component of South Korea’s economy by providing a cheap and reliable source of electricity to the country’s fast-growing manufacturing and service industries. As a result, the total capacity of coal-fired power plants has doubled to 37 gigawatts in the past two decades and coal generation accounted for the largest share (45%) of Korea’s generation mix in 2017.

National movement to phase out coal

To reduce its historic dependence on coal, the world’s fourth-largest coal importer has embarked on an ambitious energy transition to fuel its economy with more environmentally-friendly energy sources, including liquefied natural gas (LNG) and renewable energy. According to the government’s new long-term energy plan, also known as the 8thBPE (Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand), Korea aims to increase the share of gas and renewables in the generation mix to 39% while lowering that of coal to 36% by 2030. Given that nine coal-fired power plants that are already under construction are set to add a net five gigawatts of new coal capacity into the power mix by 2022, Korea’s long-term roadmap to reduce its dependence on coal will require significant investment and support from both the government and economic actors.

Figure 1. Korea’s 8th Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand (8th BPE)

President Moon Jae-in, who strongly advocated the phase-out of coal and nuclear during the election campaign, has been actively implementing follow-up policy measures to help enable the envisioned energy transition. Since the Moon administration took office in May 2017, the government has scrapped plans for two new coal-fired power plants and converted them to gas plants. The Ministry of Energy also decided to temporarily shut down ten aged coal plants during spring season and launched a new regulation that limits the maximum output of 42 coal plants across the country below 80% when the fine dust level in the atmosphere rises to a harmful point. Policy initiatives are also affecting the economics of coal generation. According to a draft energy tax code proposed by the government, Korea plans to increase the fuel tax on thermal coal by 28% while lowering the tax on LNG by 75%. Based on the analysis conducted by BloombergNEF, coal generation will still remain on-average cheaper to run than gas generation, which consequently limits the policy’s impact on the power market if the rates remain unchanged. Nevertheless, given the highly contentious nature of large tax revisions, the proposed tax code is clearly a positive indication that reflects the country’s commitment to a cleaner power system.

Limitation and outlook

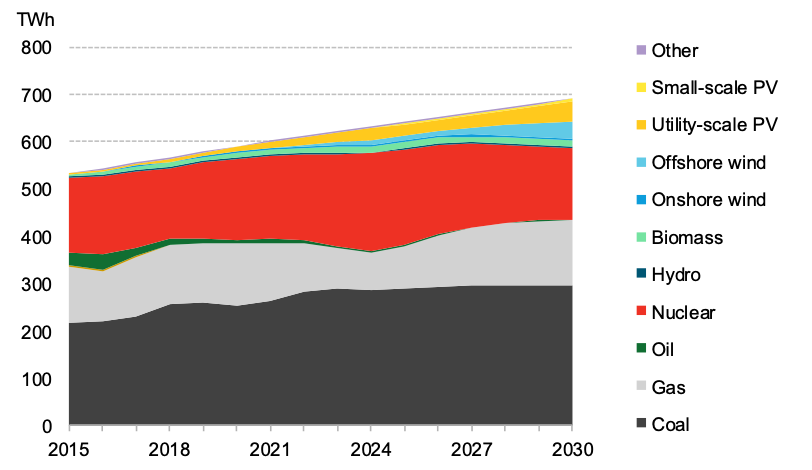

Despite the various top-down policies and bottom-up efforts that are driving the transformation of Korea’s power system, the existing inertia and the country’s inflexible power market will likely hinder the rapid transition that the nation envisions. BNEF’s New Energy Outlook (NEO) 2018, a bottom-up least-cost modelling, suggest that coal generation would continue to grow until 2027 in absolute terms as a result of the coming online of the new coal plants that are currently in the pipeline, and the little room the installed capacity leaves for new renewable energy investment. Without stronger policy intervention, coal will still be the dominant source of electricity in 2030.

Figure 2. South Korea’s power generation mix

Stronger push coming from bottom-up

Building on the momentum brought by the new central government, South Chungcheong province has taken a step further and joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA) in October 2018. As a province that is home to half of Korea’s coal-fired power plants, South Chungcheong is not only the first jurisdiction in Asia to join the alliance but also the largest coal power user to have joined the PPCA since its foundation in 2017.

As part of South Chungcheong’s ‘2050 Energy Vision Plan’, the province vowed to shut down 14 coal power plants that amount to 18 gigawatts of capacity by 2026 while increasing the share of renewable energy in its power mix to 48% from the current 8%. The decommissioning of 18 gigawatts of coal by 2026 would reduce South Korea’s coal capacity to 22 gigawatts, as opposed to the 40 gigawatts online now, creating opportunities for more investment in renewables and gas. Although the success of this roadmap will largely hinge on the central government’s willingness to revise the subsequent national energy roadmap, including the 9thBPE, the decision taken by South Chungcheong province shows that policy makers are willing to set bold objectives that will accelerate the phase-out of coal.

The ambition of the South Chungcheong province may well encourage other provinces and the national government to revise theirs and is a clear sign of the appetite for more aggressive policy initiatives. At a national level, the government should complement the temporary shutdowns and the conversion of two new coal plants to gas plants, with a more fundamental restructuring of the power market that correctly reflects the externalities of coal generation, such as the environmental and health costs, to accelerate South Korea’s phase out of coal.