By Jonathan Sims at Carbon Tracker Initiative

Ending the use of coal for power generation in South Korea by 2028 is not only possible but also the most economical option in the country’s pursuit of carbon neutrality by 2050, according to a report published last month by PPCA partner the Carbon Tracker Initiative, as well as South Korea-based Chungnam National University and NGO Solutions for Our Climate.

A complete phase-out of coal power by 2028 could result in savings of up to US$5.5 billion for the South Korean power system compared with current government plans, allowing for reductions in electricity costs for domestic consumers.

The country’s leaders have an opportunity to set a clear and ambitious phase-out deadline for coal power at the upcoming P4G Seoul Summit later this month. They should take the chance to position the power system on a trajectory for net zero by 2050 by aiming to end the use of the fuel as soon as possible.

Time for net zero alignment

Delivering net zero by mid-century will require an urgent realignment of South Korea’s power system, with greater renewables penetration needed earlier than currently planned.

The carbon neutrality pledge was made by the South Korean government late last year. Soon after, the country’s National Council on Climate & Air Quality advised Korean ministers to consider a 2040 latest end date for coal-fired power generation to achieve the aim.

But a cost-optimized analysis laid out in the End in Sight report shows that South Korea can phase out its entire coal-fired plant fleet before the end of the current decade.

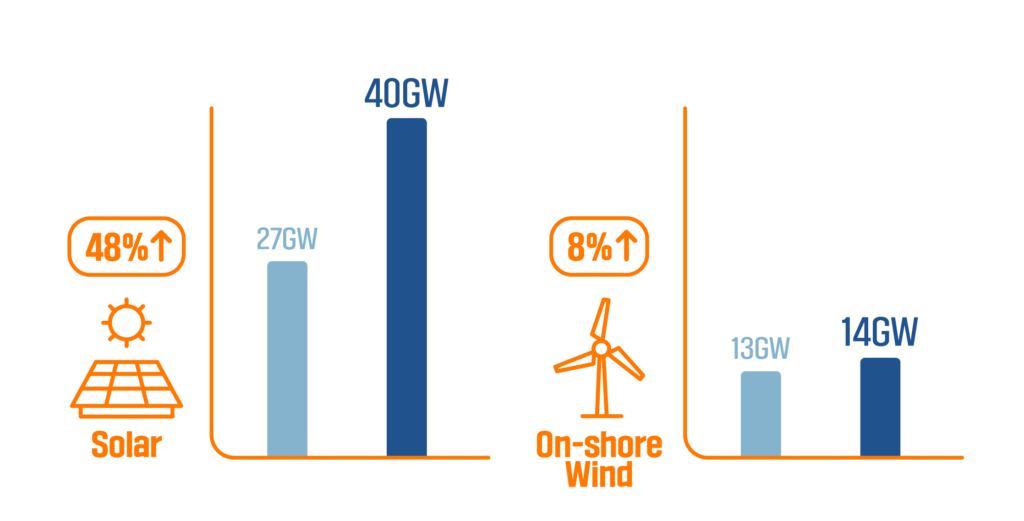

Plans to reach 54GW of installed renewable generation capacity by 2031, laid out in the country’s 9th Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand from December 2020, can be brought forward to 2028 when applying maximum growth rates in solar and wind power from recent years (32% and 27% year-over-year, respectively). 40GW and 14GW for solar and onshore wind capacity are feasible by 2028, against 27GW and 13GW put forward in the Basic Plan.

According to the analysis, if greater renewable energy production and storage coincides with the more effective carbon pricing regime currently under discussion, coal plant usage and profitability in South Korea soon begin to rapidly decline.

Coal units’ profit margins have already been squeezed in recent years. This is because the settlements received by electricity generators from the state-owned Korea Electric Power Corporation are limited to a level below the current spot power price, which has declined over the past decade.

And if coal plants’ operation hours dip owing to the increased availability of cheaper renewable energy, coal plant operators will struggle to recover costs. This will facilitate an earlier phase-out of existing coal power plants. It will also make the construction of new plants commercially unviable beyond 2030.

Earlier coal end could produce consumer savings

The accelerated deployment of renewables, with a marginal operating cost of close to zero, and an earlier coal phase-out are projected to reduce operating costs of the whole system by US$4 billion annually.

These savings will pull the estimated costs of the system through to 2050 down to a net present value of US$3.4 billion. When compared with the US$8.9 billion net costs incurred if following the 9th Basic Plan, earlier coal phase-out brings an economic benefit of as much as US$5.5 billion.

This represents a welcome opportunity for the South Korean government to use these savings to reduce costs for ratepayers.

P4G Seoul Summit

The P4G Summit will be held in Seoul over 30-31 May 2021, bringing together heads of states, CEOs and civil society leaders to reignite the discussion over the urgent climate action needed globally, ahead of COP26 in November.

As the host nation, South Korea has a clear opportunity to set the tone for discussions by following up on its climate neutrality pledge and committing to an ambitious coal phase-out programme which targets an end to the fuel’s use for power generation as early as possible.

With the economics pointing towards this being feasible before the end of this decade, the country should seriously consider embracing the chance to move to the forefront of global action in tackling the climate crisis.