By Andreas Gandolfo at Bloomberg NEF

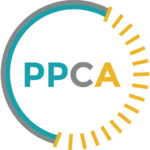

Coal has played a major role in the UK’s electricity supply over the past 20 years, generating around 30% of the country’s output in this period. The former state-owned Central Electricity Generating Board constructed most of the country’s modern coal fleet in the 1960s and 1970s, a portion of which remains operational in 2018. European policy set the first hurdle on the country’s coal fleet, with the Large Combustion Plant Directive (LCPD) leading to 8GW of shutdowns.

However, UK government policy over 2011-18 has created the conditions for the inevitable exit of coal from the country’s power mix. The mandated coal phase-out by 2025 sets a hard deadline on coal generation. Few plants will reach that date as the country’s carbon price floor has cast a long shadow on the economics of coal generators.

Figure 1. UK generation mix

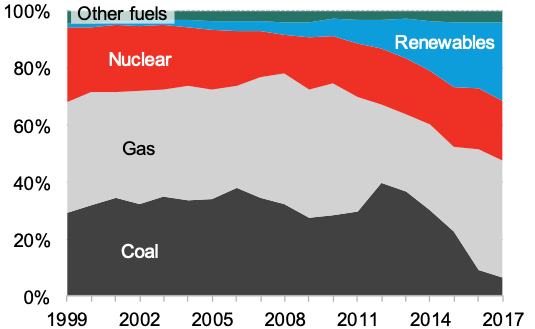

Figure 2. U.K. Coal capacity factors

Early clouds in coal’s path

Coal’s position of dominance in the UK first came into question in 2001, when the EU passed the Large Combustion Plant Directive (LCPD). This capped various emissions for existing and new combustion fuel plants above 50MW in size. Non-compliant existing plants could either choose to upgrade their facilities to meet the targets, or opt out by limiting their run-hours and shutting down by 2015 at the latest. Around 8GW of capacity, 29% of the UK’s coal fleet when the directive was passed, decided to opt out and close by the designated date.

Almost a decade after the LCPD, the EU decided to tighten its emissions regulation with the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED). Similar in nature to the LCPD, the IED gave plants three options: comply; enter a so-called transitional national plan (TNP); or opt-out.

The IED did not result in the upheaval that the LCPD brought to UK coal. More than half of the UK’s remaining coal plants opted into the country’s TNP.

UK policy decides to tackle coal

European emissions policy did its fair share to shut down a significant portion of the UK’s aging coal fleet. However, UK climate and energy policy turned out to have significantly sharper teeth. In a series of decisions over 2011-18, successive UK governments laid the ground for a coal-free future by as early as 2025.

The UK capacity market

In late 2011, the then Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC)(Now replaced by the Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy or BEIS), announced that as part of its Energy Market Reform (EMR), the UK was going to implement a capacity market.

At first glance, this policy tool does not appear to have much to do with coal’s possible demise. In fact, when DECC introduced it, many claimed that it would prolong coal’s operations in the UK However, when the economics of coal turned in late 2016 (see next section for more), they started failing to clear in the capacity market. Other projects, including many less carbon intensive new-builds and demand response, filled the gap left behind by coal plants.

As it turned out, this policy revealed that coal could be phased-out without risking energy security. By guaranteeing enough capacity in the system, the capacity market removed one of the coal industry’s main arguments in its favor, that it is essential to avoid blackouts.

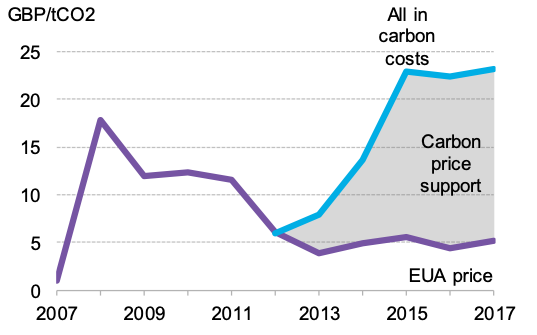

Carbon price floor

The next step in UK policy against coal was the introduction of a carbon price floor in April 2013. After years of low prices in the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme, the UK decided to set a top-up on Emission Allowances (EUAs), pushing up total emissions costs for UK fossil fuel generators. (Read more on how the UK’s carbon price floor works). A high enough price for carbon increases the cost of electricity generated by emission intensive fuels, such as coal. In turn, this makes pricier yet cleaner alternatives relatively more attractive.

The scheme introduced a gradually increasing price below which UK carbon costs cannot go (In the 2017 Autumn Budget, the UK government froze the carbon price floor at “current levels”). Until 2015, it had little effect on the operations of coal plants, as it was too low to incentivize switching from coal to less carbon intensive gas generation. However, over 2015-16, the price floor increased by a staggering 66%. All of a sudden, coal plants were out of the money, with capacity factors plummeting from 40% to 20% in a matter of months.

This development had the add-on effect of making coal plants increasingly uncompetitive in the capacity market, further worsening their already deteriorating economic position. Over 2016-17 an additional 6GW of coal shut down. Reduced run-hours, low revenue, and the prospect of having to invest in order to comply with the IED was behind their decision to shut down.

2025 coal phase out

In late 2015, the UK government announced its intention that unabated coal should cease operations by 2025. Following the conclusion of consultation processes, in January 2018 the government presented its plan for implementing a coal phase-out by October 2025.

By the time the UK confirmed its policy intention, coal had already suffered a significant blow from the rise of the carbon price floor. Nonetheless, the few plants that saw a possible future in the UK are now forced to plan their closure no later than 2025, with most expecting to do so earlier.

Figure 3. Cumulative UK coal capacity by LCPD status

Figure 4. Cost of emitting a ton of CO2 for U.K. Generators

The outlook for UK coal

Despite being allowed to run until 2025, few remaining coal plants appear willing to do so. The doubling of the carbon price has harmed the economics of coal plants. That, in turn, has reduced the clearing rate for coal units in the UK capacity market. In the last T-4 auction, held in 2017, only 2.9GW of coal managed to clear – 25% of participating coal capacity. Even these last plants will struggle to get to 2025, despite having conformed to IED regulations.

The suite of policies deployed by the UK government has been very effective in phasing out coal whilst ensuing energy security and promoting the use of lower emission generation. The carbon price floor ate into the profits of coal plants, making these old assets uneconomic. The capacity market quelled fears about what is going to replace them. Finally, the 2025 end date for unabated coal will guarantee that even those generators that manage to weather the storm will eventually close.

This coordinated policy is creating an important breathing space for two generator types:

- Gas plants have increased their run-hours, improving their economics. This has been enough to keep existing plants online, but has not resulted in new gas build, as the outlook for all fossil fuel generation is negative.

- Renewables are helped by the higher power prices that the carbon tax and increased gas burning bring. This increases the viability of commercial (unsubsidized) wind and solar projects. The state can then use subsidy budgets to fund expensive, yet promising technologies, like offshore wind.

Because of the country’s policy initiatives, the UK is on track to reduce emissions by 50% over 2015-25 – or earlier, depending on when the last UK coal plant retires.