By Tom Harries and Meredith Annex at Bloomberg NEF

Since 2010, Orsted has undergone a strategic and geographical change – stretching even to its name. Once known as Dong Energy – the ‘Danish Oil and Natural Gas’ company – it has successfully transformed itself into Orsted, a renewables-led utility. Offshore wind is the flag-bearer for its new identity, but biomass conversions and acquisitions also play a part. Not only has Orsted gone green, it has also seen increased earnings. Since its initial public offering in 2016, the firm’s market capitalization has outperformed its old oil and gas foes. Orsted now sits close to the top when compared to its new utility peers.

From oil and gas producer…

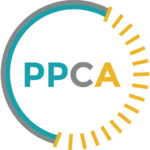

In 2010, nearly half the earnings of Orsted (then known as Dong Energy) came from exploration and production or thermal generation activities (In 2010, 49% of Orsted’s Ebitda was from exploration and production or from thermal generation activities. The rest was from other activities, especially sales, distribution and trading). Around 70% of its power plants burned coal, gas or oil (Figure1).

Figure1 : The evolution of Orsted’s power assets

By the time of its name change, this share had reversed – over 70% of Orsted’s 2017 power fleet was renewable. And the evolution is far from over. By 2020, the share of its fleet burning fossil fuels is expected to reach a mere 10%. That means 90% will come from clean energy sources: biomass and waste burning plants and onshore and offshore wind farms.

This transformation should see Orsted’s carbon emissions from power and heat fall sevenfold: from around 350gCO2/kWh in 2010 to around 50gCO2/kWh in 2020 (Taken from Orsted’s Capital Markets Day 2018 presentation. Excludes oil and gas). Plus, the firm has sold off its oil and gas production assets – making the drop in corporate emissions even starker.

…to offshore wind major

What made this possible was a pivot to renewables, and particularly to offshore wind. In fact, the firm is now Europe’s leading offshore wind developer.

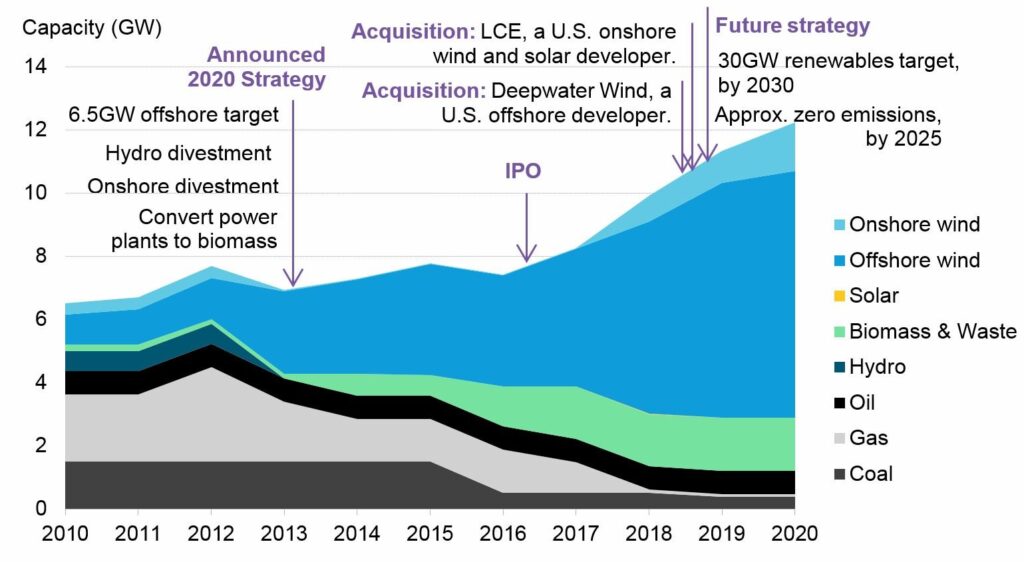

Orsted is on course to have developed just under eight gigawatts of offshore wind capacity in 2020 – an eightfold increase from where it was in 2010. And this market-leading position is unlikely to change anytime soon. Already, the firm has an existing and planned offshore wind project pipeline in Europe that is more than double the size of the second-most prodigious developer: Vattenfall.

Figure 2: Top 10 offshore wind developers in Europe

By the time of its name change, this share had reversed – over 70% of Orsted’s 2017 power fleet was renewable. And the evolution is far from over. By 2020, the share of its fleet burning fossil fuels is expected to reach a mere 10%. That means 90% will come from clean energy sources: biomass and waste burning plants and onshore and offshore wind farms.

This transformation should see Orsted’s carbon emissions from power and heat fall sevenfold: from around 350gCO2/kWh in 2010 to around 50gCO2/kWh in 2020 (Taken from Orsted’s Capital Markets Day 2018 presentation. Excludes oil and gas). Plus, the firm has sold off its oil and gas production assets – making the drop in corporate emissions even starker.

…to offshore wind major

What made this possible was a pivot to renewables, and particularly to offshore wind. In fact, the firm is now Europe’s leading offshore wind developer.

Orsted is on course to have developed just under eight gigawatts of offshore wind capacity in 2020 – an eightfold increase from where it was in 2010. And this market-leading position is unlikely to change anytime soon. Already, the firm has an existing and planned offshore wind project pipeline in Europe that is more than double the size of the second-most prodigious developer: Vattenfall.

Figure 2: Top 10 offshore wind developers in Europe

While most offshore wind activity is located in Europe, Orsted is also active internationally.

It is an early entrant in Taiwan, where it has lined up 1.9 gigawatts of capacity as the country looks to replace a retiring nuclear fleet with renewables and gas.

Orsted has also entered the US initially by replicating its European strategy of acquiring sites for offshore wind farms. But in November, it changed tack and acquired one of its key US rivals: Deepwater Wind. The acquisition includes the only operating offshore wind farm in the US, as well as a number of projects that have secured long-term offtake agreements and several new sites. As a result, Orsted is now in a more competitive position in upcoming offshore wind auctions across the Eastern seaboard.

All in all, this makes Orsted not just the largest offshore wind player in Europe – but also a leader globally.

Underpinning it all: a transforming strategy

This chain of events was started with a new strategy released in 2013. The plan, released in February of that year, established that by 2020 Orsted would divest non-core assets and invest its earnings from upstream oil and gas into offshore wind and biomass.

Five years later, it is on course to meet its renewables goals. In addition to the eight gigawatts of offshore wind that BloombergNEF expects Orsted to commission by 2020 (exceeding its target of 6.5 gigawatts), the firm has divested onshore wind and hydro assets (Figure 1) and is on track to have either divested or converted most of its coal and gas power plants to biomass by 2020.

Of course, not all has gone to plan. Orsted has renegaded on its onshore wind plans: after selling off assets, it has re-entered the industry in the US with its acquisition of Lincoln Clean Energy in 2018 – which primarily develops onshore wind and solar. It also didn’t keep to its initial intentions around oil and gas. Orsted started to raise cash by selling shares in its offshore wind farms to institutional investors, such as pension funds. This meant the firm did not need to rely on exploration and production activities to fund new business. So, in 2017 it sold its upstream oil and gas business, transforming Orsted from a fossil fuel company to a renewable energy firm.

The change has been cemented in a name: once called Dong Energy (Danish Oil and Natural Gas), the firm is now branded Orsted in honor of a Danish scientist who discovered that electric currents make magnetic fields.

Renewables driving earnings at no expense to company value

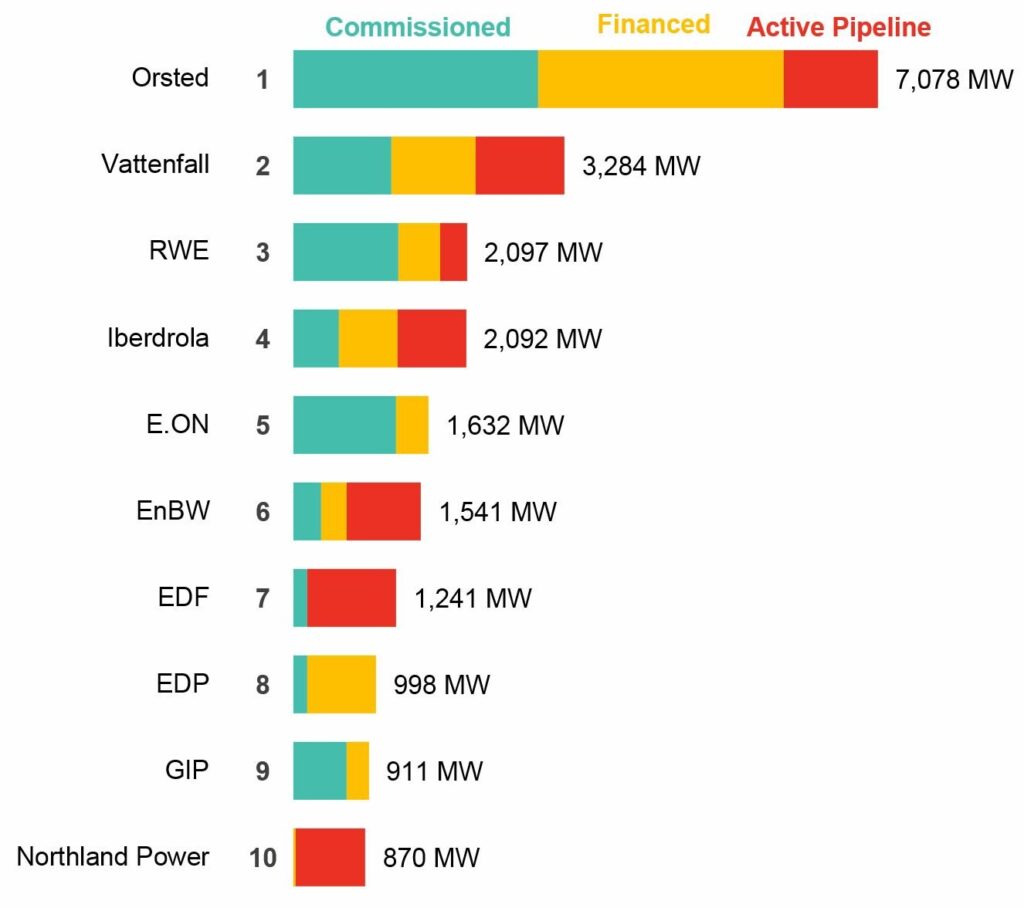

The transformation is clear in Orsted’s earnings. Thermal generation and oil activities (exploration and production) accounted for well over half of Orsted’s Ebitda before 2010. Yet earnings from its wind development business have been rising steadily. In 2017, wind accounted for 91% of Orsted’s total Ebitda while fossil fuel-based activities – from generation or from exploration and production – were a mere 1% of total earnings.

Figure 3 : Orsted Ebitda by business segment

Note: Depicts unadjusted Ebitda. Wind power was only separately reported starting in 2010. The lower performance in 2012 was largely due to Orsted’s “customers and market” business unit.

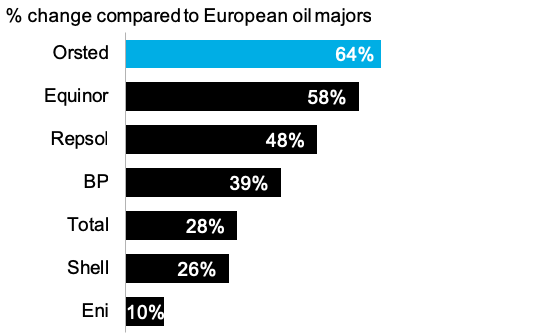

What’s more, Orsted’s transformation seems to have paid off in terms of company value. Orsted’s market capitalization – or “market cap” – captures the total value of the company’s stock currently held by shareholders; Orsted’s has risen 64% since its IPO in 2016. This is greater than the gains seen by the six largest independent oil companies in Europe, which essentially makes up Orsted’s pre-transformation peer group.

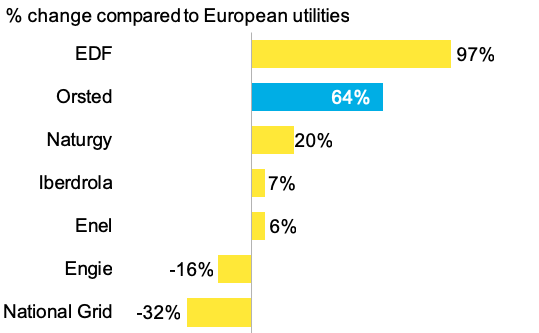

Now, in its current form, Orsted more closely resembles a utility – and even here the firm fares well. Orsted currently tops the list of largest utilities in Western Europe by market cap, according to Bloomberg equity data. Of the largest European utilities, only EDF has seen its market cap grow more than Orsted’s since the IPO – while others in the region have seen their market cap fall or barely change.

Figure 4: Change in market capitalization since Orsted IPO, compared to peers

Note: Shows change in market capitalization from June 9, 2016, to November 1, 2018. Negative value indicates that market capitalization has fallen over this time period. Naturgy was formerly known as Gas Natural.