By Atin Jain at Bloomberg NEF

India’s coal power generation story started 98 years ago with the commissioning of Hussain Sagar Thermal Power Station in Hyderabad in 1920. India kept adding coal capacity at a gradual pace after that and had reached 71 gigawatts of coal power generation capacity by 2007. Then, over the subsequent 11 years, an explosion of capacity additions resulted in more than 130 gigawatts of new coal plants coming online.

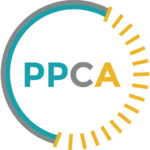

The last peak annual capacity additions was 2015, when 19 gigawatts of coal power plants were added in India. Annual net additions have been declining since then. In 2017, India added more renewable power generation capacity than coal fired capacity for the first time ever and is expected to repeat the feat in 2018. This is the beginning of a new trend and BloombergNEF expects renewables will always outcompete coal power on an annual build basis in the future. Today, 196 gigawatts of grid-connected coal-fired power stations supply about three quarters of the total electricity requirement in the country.

Figure 1 – Net annual power generation capacity additions in India

Rising fuel costs, low fleet utilization and air pollution regulations are making coal power economics unattractive

Coal became the workhorse of the power sector due to the promise of low-cost power supply the country desperately needed. However, the economics of coal power generation are under stress due to the rising costs of coal supplies, a drop in the capacity utilization factor (CUF) of power plants and new emissions regulations.

Transport costs make up more than a third of the landed cost of coal supplied to the power plants. These costs have more than doubled over the last 10 years, leading to an increase in the power generation costs. In future, we expect transport costs to increase faster than the basic run-of-mine coal price. This will continue to increase the cost of power generation from coal plants.

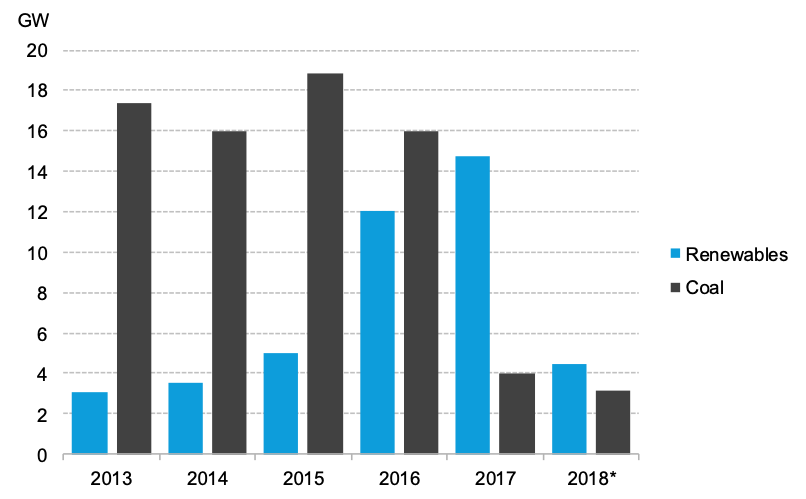

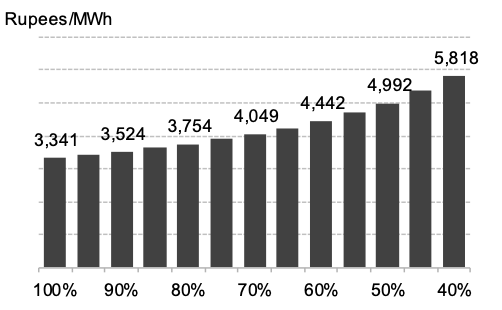

The coal fleet utilization dropped from 77.5% in fiscal 2010 to 60.6% in 2019, due to excessive capacity build out and slower-than-expected growth in power demand. A decrease in CUF of a coal plant leads to an increase in the cost of power generation. BNEF estimates that the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) of a new Indian coal power plant increases by 18% with a drop in CUF from 80% to 60%.

Figure 2 & Figure 3 – Capacity utilization factor of Indian coal fleet (left) and impact of changing capacity factors on the levelized cost of electricity of coal plants (right)

New emission mandates from the government aimed at reducing sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and particulate emissions from power plants will require the installation of emission control equipment such as flue gas desulfurization plants, selective catalytic reduction units/low NOx burners, electrostatic precipitators etc. at the power plants. We estimate that these installations can increase the levelized cost of electricity from coal by as much as 9%, depending on the choice of emission control technologies.

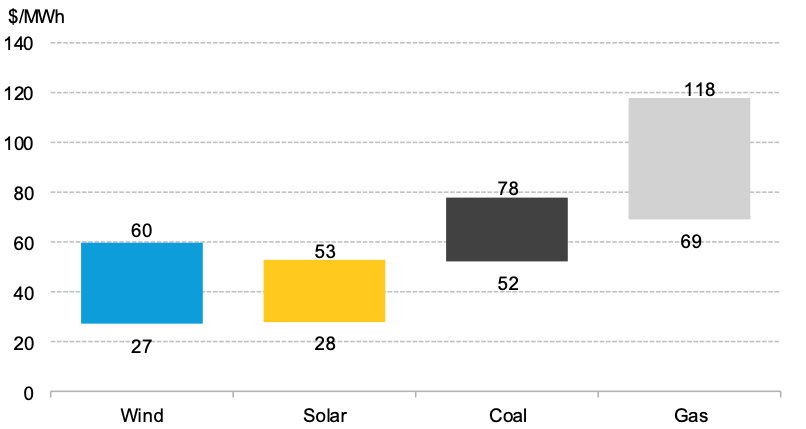

New renewables are already cheaper than new coal power in India

Solar and wind power are already the cheapest form of new power generation sources in India. Some of the cheapest new-build solar and wind farms are even cheaper than running many of the existing coal-fired stations in India. Power from new solar and wind plants in India is being procured at fixed nominal tariffs for 25 years. Conversely, the coal power tariff usually increases every year due to higher energy charges (such as landed fuel costs) of the generating stations.

Figure 4 – Levelized cost of electricity from competing power technologies in India

Renewables will add more generation capacity than coal annually in future

The long-term outlook for coal power generation looks weak as the challenges facing the coal sector will persist in future. The economic competitiveness of renewable power sources as a bulk power generation source has led to cancellations of many proposed coal power plants in India.

The demand for power will continue to grow in future, but new coal capacity additions and an explosive growth in competing renewable power technologies like solar and wind will lead to a persistent supply glut of coal power. This will keep the CUFs of Indian coal fleet suppressed in the short term.

Around 36-40 gigawatts of coal projects are currently under construction and will come online in the next five years. Coal capacity additions is expected to slow down after that. While capacity additions will ease off, the retirements of coal fleet will accelerate. The Central Electricity Authority in its National Electricity Plan 2018 expects 48 gigawatts of coal-based generation capacity to retire by March 2027.

Due to the air pollution concerns, coal projects are not expected to go for life extensions through renovation and modernization, but will be retired at the end of their economic life.

Figure 5 – Projected gross capacity additions and retirements of Indian fleet

While coal projects already under construction will come online, albeit with a delay in commissioning, it is becoming increasingly difficult to conceive and plan for new coal projects. Land acquisition for coal power projects (and mines) is becoming more difficult due to local community protests. Sourcing water and fuel supply for the projects is another major hurdle. Almost all under-construction coal projects are delayed, with many of them overdue by more than five years. The interest rates for long-term debt to coal projects have gone up and surpassed those for renewables in the last few years as lenders factor in these issues when deciding on the premiums. The bad experience of the banking sector with non-performing coal assets has further led to a reluctance amongst the lending community to finance new coal projects.

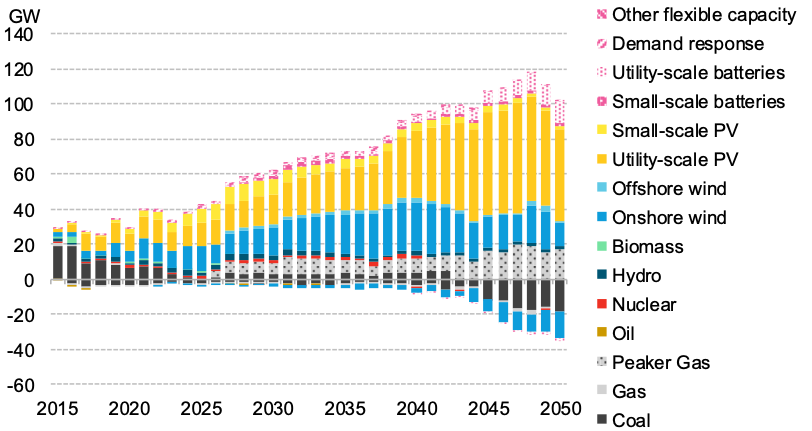

Renewables will supply three quarters of India’s total electricity demand by 2050

Based on our long-term economic forecasts of India’s power system, we expect renewable energy sources (including hydro) can supply 75% of India’s total electricity needs by 2050. Solar and wind are expected to supply a third each of the total power demand. The share of coal will drop to just 14% in 2050 from 75% in 2017.

Figure 6 – Expected electricity generation from different power generation sources in India

Supply-chain constraints are adding to the power plant operator woes

Indian coal power sector faces regular supply-chain issues. Power plants do not receive the full quota of fuel under their supply agreements with Coal India and other domestic suppliers. The miners are unable to meet their production targets. The government wanted Coal India to produce 1 billion metric tons of coal by fiscal 2020. However, the company has pushed back this target to 2026 due to India’s rapidly evolving electricity supply mix, air pollution reduction targets, challenges in land acquisition and slow industrial demand.

The supply-chain issues are not just restricted to production challenges. Indian Railways is regularly confronted by train shortages and network constraints. Indian coal plants are unable to maintain enough fuel stock due to these reasons and many Indian coal power plants are forced to shut down due to coal shortages. The plant closures and fuel shortages have led to power cuts in many parts of the country in recent times. Even the spot power prices in wholesale markets went up to record highs due to low power generation from coal plants and high seasonal power demand.

The government last year ordered state-owned power companies to stop thermal coal imports and was trying to convince IPPs to source their coal needs from domestic sources only. But the supply shortages prompted many utilities and IPPs to resume coal imports to meet their fuel needs. Contrary to government ambitions, India’s thermal coal imports are growing at the fastest pace in the last three years and went up by 35% in July-September 2018 over 2017. This was during a time when the international coal prices were at a six-year high.

Leading coal power producers and miners are investing in renewables

Major Indian and international companies are realizing the long-term implications of cheap renewables on the future power mix of India and are looking to invest large amounts of capital to set up solar and wind power plants in the country. The ever increasing challenges in building and running coal plants are just making these decisions easier for the companies. Some of the most striking plans for renewable deployment in the country come from India’s largest power generating utility – NTPC Ltd. – and world’s largest coal miner – Coal India Ltd.

NTPC currently has 46 gigawatts of coal plants and is looking to add another 19 gigawatts of thermal capacity over the next five years. But these plans are dwarfed by the company’s ambition to add 32 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity by 2032, which would constitute a quarter of its total fleet of 130 gigawatts by 2032. NTPC used to conduct auctions for renewable power and procure power from IPPs due to government mandates. Now, the company is itself participating as a developer in auctions by other bidding agencies and plans to utilize its expertise in power project development. Recently, Coal India and Neyveli Lignite Corp. announced a partnership to set up 3GW of solar power capacity.

The National Tariff Policy 2016 suggests that any coal based power producer should also set up an equivalent renewable energy capacity as a part of their renewable generation obligations. In future, this should also lead to a higher deployment of renewables from other coal IPPs and utilities.

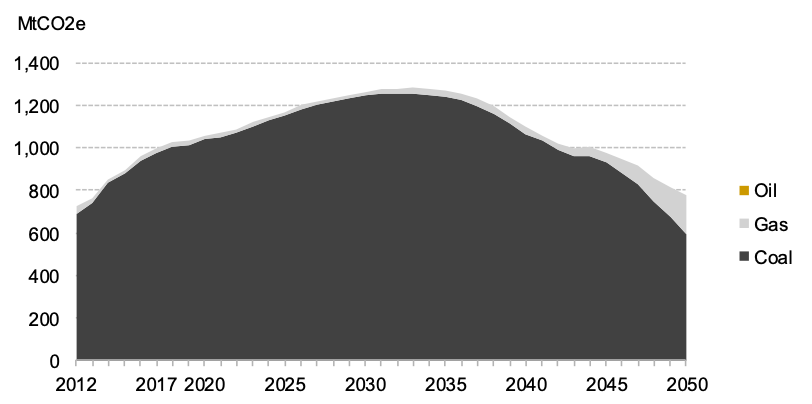

India can achieve peak power sector carbon emissions in early 2030s

The surge of renewables and a retreat of coal power in the future will result in India achieving peak power sector carbon emissions in the next 15 years, even without additional policies. Carbon emissions are expected to go up by 29% from 2017 levels and peak in 2033. By 2050, emissions would be 22% lower than in 2017.

Figure 7 – Power sector carbon emissions in India

These developments give very strong and clear signals about the inevitable transition of India’s fossil fuel power generation to a clean and sustainable power mix. This transition to cleaner power mix will be faster than previously anticipated and will create long-term opportunities for investments in clean energy technologies.