By Natalia Castilhos Rypl at Bloomberg NEF

Chile has the most coal-dependent electricity mix in South America. Coal-fired generation, most of which came online over the last decade, has helped fuel one of the region’s most dynamic economies and its energy-intensive industries, such as a copper sector that now accounts for a third of all power consumption.

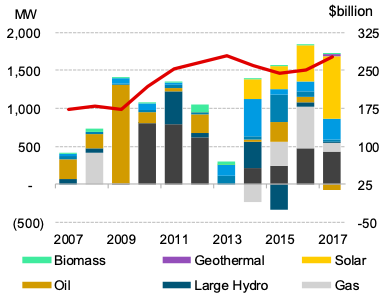

Powering considerable economic growth

Chile’s economy has grown more than 50% over the last decade and the country now has the highest GDP per capita of the continent. New coal plants have met most of the added electricity demand over the period. Coal’s installed capacity has doubled since 2010 and currently provides 22% of the total capacity. In a given year, Chile’s 5GW of coal plants produces about 40% of the country’s total electricity generation.

Figure 1. Chile net capacity additions per technology and GDP

Figure 2. Chile net capacity additions per technology and GDP

However, the Chilean government also saw the importance of developing renewables to mitigate the increasing emissions intensity of the country’s generation. The country’s exceptional solar and wind resources, combined with the drop in the cost of renewable energy technologies, confirmed the government in its position. The country has one of the region’s most sophisticated power sector regulatory environments, which enabled it to develop its renewables support. Private companies are active across power generation, transmission and retail. Electricity trades on a wholesale power exchange with nodes indicating the value of electricity in different locations. Frequent tenders for long-term power purchase contracts, with a design that favours renewables, successfully transform the interest of developers into large investment volumes.

In 2013, the government introduced a series of regulations to support renewables that resulted in the addition of 3.7GW of renewables capacity. All utilities with more than 200MW of generation capacity, under Law No. 20.527, must ensure 20% of that is renewables by 2025, twice the earlier target. A carbon tax set at $5 per ton of CO2 emissions for power generators was also introduced in 2014. The first annual tax receipt covering 2017 emissions stood at $191 million, 94% of which paid by power generators using fossil fuels. However, the effect of the tax on the power sector was somewhat blunted through two clauses. Firstly, the carbon tax is not taken into account in determining dispatch, preserving the position of coal generators in the merit order. Secondly, coal generators are compensated whenever the cost of the tax is higher than their marginal cost which resulted in an around 15% discount in payments for the year 2017. Whilst Chile’s carbon tax is one of the first in the region, it fails to significantly impact the place of coal in the power mix under its current framework.

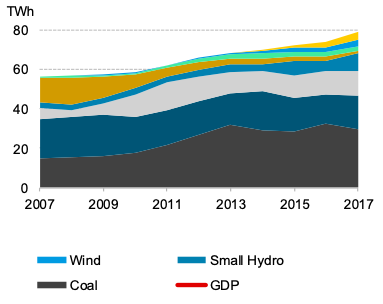

The government completed these measures in 2014 with a reform of Chile’s technology-neutral electricity procurement auctions. These have become renowned for record low bids from clean energy generators that outcompeted fossil fuels. The new rules divided the auctions into time blocks, with generators competing to deliver electricity over that time window alone in a PPA awarded for 20 years. This was particularly successful in ensuring the maximization of solar development as the technology beats any other for delivering daytime electricity thanks to the country’s exceptional solar resources. However, the considerable improvement in economics for onshore wind have also meant renewables have also won most of the contracts on offer outside of the time blocks that favour solar. In two of the past three auctions, companies bidding with renewables portfolios were the only ones to win contracts. Chile has recorded $10 billion of clean energy investment since 2013.

Figure 3. Auction results by size, price and share of renewable winners

Chile’s elongated power markets

The surging growth of renewables, combined with Chile’s sophisticated and regionally differentiated wholesale power market, have highlighted the integration challenges of an ambitious energy transition. The share of renewables in Chile’s electricity generation jumped to 24% in 2018, from 9% just six years earlier, as a result of the government’s effective policy mix.

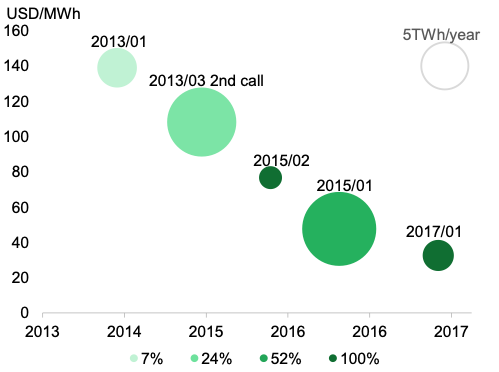

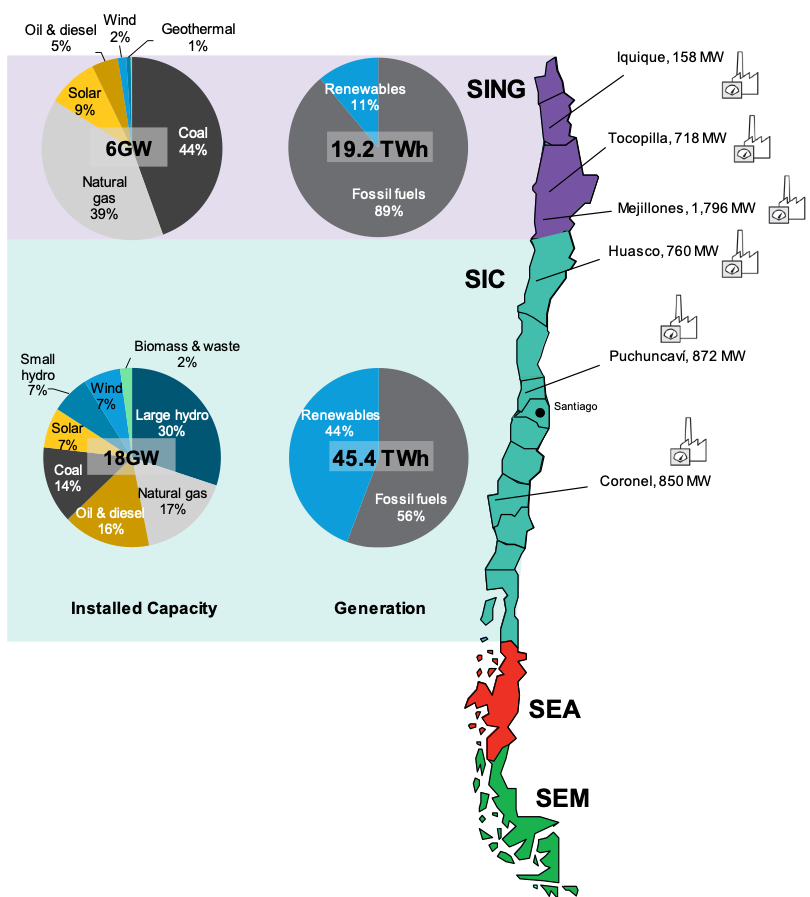

Chile’s power grid used to be divided into four main systems, with little or no interconnection between them. In the north, the Sistema Interconectado Central (SIC) and Sistema Interconectado del Norte Grande (SING) subsystems have to meet most of the country’s energy demand. The SIC serves 90% of the population, whilst SING has a high concentration of industrial activity, in particular mining.

Figure 4. 2017’s installed capacity, generation and coal assets

The north of the country covered by the SING system is where the Atacama Desert is located. It receives some of the strongest, most consistent sunshine on Earth. The Cerro Dominador concentrated solar power project, Latin America’s first, is being built in the Atacama Desert. It will allow for stored heat to be used for power generation at night. However, the vast majority of renewables development to date has happened in the SIC, closer to residential and commercial demand centers, with 93% of all wind and 70% of solar projects commissioned in the area.

There is lack of transmission capacity, in particular interconnecting the four systems. This has rapidly led to the curtailment of renewables generation, which reached 16% of renewables generation in 2017. A first major step toward improving the situation was made in November 2017, when the 600-km transmission line that connects the SING and SIC was commissioned. The $880 million investment has helped reduce curtailment, but Chile is investing considerably more in the expansion of its grid. A second interconnection between the two largest systems is due to be commissioned in 1Q 2019, and the government launched a grid expansion tender program in 2017 that will require around $2 billion of investments for the development of more new lines.

Chile’s path to decarbonization and the outlook for coal

In response to the surge in renewables development, the share of fossil fuels in the generation mix fell from 66% to 54%, with oil and diesel dropping the most. Coal contributed 37% in 2017, below the 46% peak of 2013. This lower share, however, is a result of better availability of hydro generation. The share of coal is expected to increase once again in 2018 as less rainfall was recorded. With much of the coal capacity only just commissioned, BNEF expects policy intervention will be needed to significantly reduce the role of coal in the generation mix in the short to medium term, and the government seems prepared to deliver it.

In 2016, Chile released its long-term energy plan, which sets a target for renewables to account for 70% of electricity by 2050. In January of 2018, AES Gener, Colbún, Enel and Engie, the four companies that own Chile’s coal assets, made a voluntary agreement with the government committing to not invest in new coal projects that do not integrate carbon capture and storage systems. The agreement also stipulates that the four companies will work toward the decarbonization of their existing assets along with the government. At first, a series of round-tables bringing together the various stakeholders of Chile’s power sector has been held throughout 2018 to develop criteria that should inform the coal phase out challenge, including consideration of transmission constraints and the potential of various technologies to replace coal. The government’s current plan is that the four utility companies with coal power plants will then voluntarily propose their own coal phase out pathways, which will then be aggregated and analysed. A schedule for the retirement or conversion of Chile’s coal plants is due in 1Q 2019, with the target year likely to fall between 2030 and 2040.

A preliminary study on the future of the Chilean grid without coal concludes that an extra 5GW of capacity would have to be deployed by 2040 compared to a scenario where no new coal capacity is added and existing plants are retired at the end of their lifetime. The mix of technologies would lean towards gas over the coming decade, before a mix of solar, wind, pumped hydro and batteries take over. This transformation would require more investment into new generation and grid assets.

The signal from the Chilean government that it is serious about finding a way out for unabated coal, combined with efforts to mobilize record investment into clean energy and the grid, has set the country on the path of a coal phase-out at a pace that was unimaginable some years ago. Shortly after the announcement of the decarbonization plan, Engie (a member of the Powering Past Coal Alliance), requested an authorization to retire two coal units totalling 170MW of capacity located at Tocopilla, as they have become uneconomical due to their age. The plants are going to be decommissioned as soon as the transmission line Cardones-Polpaico becomes operational, which will increase the flexibility of the Chilean grid and allow renewable generation to better flow within the country. In parallel, Engie is soon going to commission the last coal power plant in the country, a 375MW plant located at Mejillones.

Air pollution is also playing a critical role in driving Chile’s coal plant decommissioning objectives. The country’s old coal plants in particular have been responsible for regional air pollution. In August 2018, the regions of Quintero and Puchuncaví suffered a major environmental crisis as air pollution reached levels toxic to local communities. The government responded by forcing one coal unit at the AES Gener 884MW coal power plant to shut down temporarily.

Integration with the energy systems of other countries in the region will additionally play an important role in delivering Chile’s decarbonization strategy. Chile’s neighbor, Argentina, has recently increased production of unconventional gas and started to export to Chile for the first time in 11 years. Chile’s minister of energy, Susana Jimenez, also plans to expand interconnection, especially with Argentina and Peru, to increase the flexibility of the grid. Currently, Chile has only one international electricity transmission line with Argentina, inaugurated in 2015.

Consensus across party lines points to continued ambition

Whilst there are ideological differences between Chile’s main political groups, the country’s dedication to mitigating climate change is solid. The current president, center-right leader Sebastian Piñera, took office in March 2018 and immediately confirmed the decarbonization policy of outgoing center-left President Michelle Bachelet. This will now be complemented through the development of a new climate change law.

The 2018-2022 energy agenda of the current administration set decarbonization as a top 10 priority. It has added a new law on energy efficiency; increased the capacity thresholds under which renewables generators can access the advantages granted to distributed generation; and set a goal of increasing EV penetration tenfold by 2022.

Chile ranked 1st in BloombergNEF’s 2018 Climatescope report, a survey of the attractiveness of 103 emerging markets for clean energy investors. This was achieved thanks to the combination of ambitious renewables policies, power sector regulation that favour investors, and a track record of clean energy investments. The solutions that will allow Chile to maintain its standing as a hotspot for clean energy investment globally are also those that will allow the country to accelerate the phasing out of coal generation and meet its decarbonisation objectives. Expanding interconnections between Chile’s grid and introducing more sophisticated power market regulations will be critical in providing the grid flexibility and resilience needed to allow for higher levels of renewables penetration.