The serene waters of the Lusatian lake district in East Germany, lined by golden sand and winding cycle paths, is far removed from its history as a network of opencast mines. Located just over one hour from Berlin by train, the area that used to be a hotbed of coal mine activity has now been transformed into a vacationer’s paradise, complete with restaurants, hotels and adrenaline-pumping activities.

Factories for battery cell production are also being proposed for Lusatia, as the region transitions away from coal and seeks new investment and jobs in growing areas of the economy, such as electric vehicles and renewable energy.

In the U.S., the fast-growing industry for rooftop solar also provides a wealth of new job opportunities for ex-coal workers. Some 250,000 people are employed by the solar industry – an increase of 168% on 2010 levels, according to the National Solar Jobs census 2017. More than half of these employees install solar panels – a role that has many parallels with working in the coal sector, such as technical capability, physical competence and attention to safety.

The number of wind turbine technician jobs in the U.S. will almost double by 2026, as the market for wind energy continues to grow, according to Xinjiang Goldwind Science & Technology Co. The company has a training program in the U.S. to teach technical and safety qualifications for the deployment of wind turbines, and recognizes the parallels between the skills required to work in the fossil fuel industry and those required to work in wind energy.

“Working as a miner involves operating and maintaining equipment and conducting repairs as needed, which is also the case for turbine technicians,” David Sale, chief executive of Goldwind Americas wrote in an e-mailed statement to Bloomberg. “The transferability stems from miners’ aptitude for technical work and thinking, and their familiarity with working in line with important workplace safety measures,” he explained.

Phasing out coal is a contentious topic in countries like the U.S. and Germany, where many people continue to be employed by the industry. Particularly as the coal sector is backed by influential advocates such as U.S. President Trump, who made reviving the coal industry a central part of his campaign pledge. In Germany, the leader of coal-producing state Brandenburg, Minister President Dietmar Woidke, advocates for a very late coal phase-out, due to the social and economic implications of closing down power plants too quickly with no time to provide alternative avenues of employment.

However, new industries like renewable energy can provide greater job stability as countries increasingly seek to clean up their power systems. This article explores some viable alternatives to working in coal.

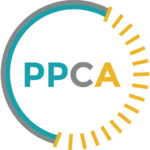

Figure 1. Coal accounts for less U.S. power generation year-on-year

Germany’s coal phase-out

“Employment issues are at the core of why coal is politically-sensitive in Germany”, said Alexander Reitzenstein, policy advisor at E3G, a Berlin-based think tank for the environmental sector. The government is moving to gradually phase out coal mining and coal-fired generation in order to achieve its carbon reduction commitments, but doing so is often at odds with protecting the livelihoods of many of its electorate.

In the state of Brandenburg, where elections will be held in 2019, around 8,000 people are employed in the lignite industry. Coal jobs are highly unionized in the area and the election outcome is likely to be heavily influenced by politicians’ approaches to the coal phase-out. Proposals by politicians such as Peter Altmaier, Germany’s Minister for Economy and Energy, to invest in large-scale battery cell production factories and innovation hubs for new technologies, are a response to the growing need for new employment opportunities and regeneration of the area.

Germany’s Coal Commission, established in the government’s coalition treaty, is tasked with setting a coal exit date and coming up with a path to reaching the 2030 climate targets. It has 1.5 billion euros allocated to invest in education, re-skilling and infrastructure to reach those targets – money which could be spent on retraining ex-coal workers in new industries. The date for Germany’s coal phase-out will now be decided in early 2019 and “is currently most likely to be set somewhere between 2035 and 2040,” Reitzenstein told BloombergNEF in an interview.

Around 30,000 people are employed in Germany’s lignite and hard coal sectors, compared to the 340,000 jobs in renewable energy – but coal jobs are highly-unionized and the sector has a long history of debating on issues of societal importance. Closing coal mines and coal plants will also impact other related sectors, such as energy-intensive industries, and could potentially jeopardize jobs there too, say local politicians.

West Germany’s successful transition from the hard coal mining that drove its industrial growth in the 1950s and 60s to a more service-based economy could be taken as a useful blueprint for what needs to be done to phase out lignite in the country’s East, although that region “is structurally-weaker, there are more social and economic issues, and less industry,” said Reitzenstein. The hard coal phase-out also occurred gradually over decades, so there was more time to create alternative sectors and to gain societal consent.

Some mines in West Germany were filled up to be used as farmland thanks to good soil quality, and there are also examples of businesses that previously served the coal industry now serving renewables, said Reitzenstein. For example, Bochum-based Eickhoff Group has diversified away from mining technology to manufacturing wind turbine gear boxes.

The Zollverein coal mine complex in Essen shows the significance of the coal mining industry to European industrialization and is a source of new jobs and tourism revenue. Visitors can tour the former coal-mining site – now designated as a UNESCO world heritage site – and learn first-hand about the coal mining industry, with tours of the pits, coking plants and even the miners’ housing.

Investment needed

East Germany needs “concrete investments” such as in battery facilities, and “public infrastructure investment”, in order to attract private investment and to convince local stakeholders that the federal government is prepared to invest in regeneration, said Reitzenstein. The region views structural change negatively, because “before 1990 the region was very important for coal with more than 100,000 workers, but after reunification, the whole industrial area collapsed,” he explained.

In addition to new employment opportunities, policy needs to provide strong social support schemes to provide for older workers who may be less able to retrain, he added. Some estimates are that by 2030, two-thirds of coal miners will be retired anyway, so a relatively small amount of people could be seeking new employment, according to E3G.

Swedish utility Vattenfall told BNEF that it will be able to manage the employment reduction as a result of coal plant closure entirely through early retirement. The utility aims to shut down or use alternative fuel for its remaining coal-fired combined heat and power plants in Germany and the Netherlands by 2030, in order to comply with regulation and reduce its CO2 emissions. In Berlin alone, the company will invest 1 million euros per day to transition to new energy and phase out coal, Tuomo Hatakka, senior executive vice president for heat at the utility, said in an interview.

The Drax coal power plant conversion in the U.K. is an example of how converting facilities to run on less-polluting fuel can be a way of retaining jobs. The 4,000 megawatt facility now has four units powered solely by wood-chip combustion, and previous coal plant workers have been retrained in handling biomass, Will Gardiner, chief executive of Drax, told BNEF in an interview. Drax employs 900 people at its plant in Yorkshire and indirectly supports 6,000 jobs in the region through its supply chain.

Alternative employment

Momentum is building in Lausitz to create alternative opportunities aside from work in the coal sector. A collaboration between Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute and the University of Senftenberg and Cottbus in Lausitz is developing a research cluster around new technology such as energy storage and micro-electronics, aiming to attract new businesses and investment to the area, said Reitzenstein.

And in South Brandenburg, Dekra SE acquired the Klettwitz racetrack last year with the aim to develop and test autonomous driving. The project aligns with Germany’s automotive industry and its development of electric and autonomous vehicles, and could further propel regional expertise in new technology.

The scale of Germany’s automotive industry and associated supply chain could also act as a good foundation for battery development. Volkswagen is becoming more open to producing the battery cells for electric vehicles under the leadership of Herbert Diess, with some reports suggesting that the company’s pilot cell facility in Salzgitter may be expanded.

Parts supplier Continental AG is also considering moving into battery cell production, and spinning off its power train division, according to Bloomberg News. Elsewhere, LG Chem’s plan to open Europe’s largest lithium-ion battery factory in the Polish city of Wroclaw could also help propel European knowledge of battery cell production, particularly given its proximity to Germany’s auto industry and coal phase-out. The LG Chem factory will employ 2,500 people and produce 100,000 EV batteries annually, according to a Reuters articlefrom last November.

The spacious and flat landscape of Lausitz is also conducive to building wind farms and solar parks, said Reitzenstein. In Brandenburg alone, around 20,000 people work in renewable energy and there is lots more potential for wind farm development, said Reitzenstein. “Jobs in renewable energy outnumber those in coal, sometimes by tenfold in Germany,” he told BNEF. In the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, where renewable energy is much more developed, there are around 46,000 jobs in renewables, versus just 9,000 in lignite.

Expansion of existing industry in Lausitz would also increase employment opportunities for ex-coal workers. BASF SE has a chemical industry facility with room for expansion, and Hamburger Rieger GmbH owns a paper-making facility, according to Reitzenstein.

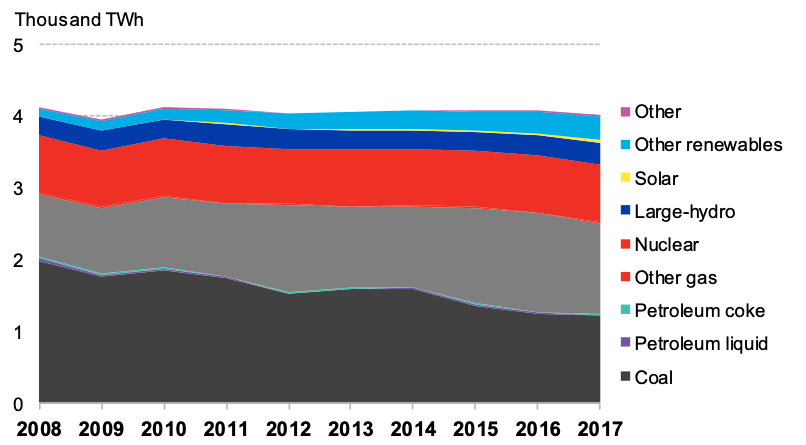

Figure 2. U.S. coal mining work is in decline

U.S. solar

The U.S. rooftop solar industry is expanding quickly, including in states with a large economic presence in coal. Indeed, as the economics of coal become increasingly less attractive and more U.S. coal plants are shut down, the number of jobs in renewables is rapidly outpacing those of the incumbent power sector, including coal. U.S. solar and wind industries currently employ around 475,000 people in the U.S. – three times as many as the coal industry, according to Goldwind. The two industries with highest projected job growth by 2026 are both in renewable energy, projects the U.S. Labor Department.

Rooftop solar companies, Sunrun and Vivint Solar, each employee around 4,000 people in the U.S., with a significant portion of these engaged in service and installation work. Both companies have recruited people previously employed in the coal industry. “There is overlap between the knowledge and experience coal miners possess about tools and machinery and the equipment used in PV installation,” Chad Herring, vice president of talent at Sunrun, told BNEF in an emailed statement. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that 65-70% of jobs in coal mining are not industry-specific, so re-training ex-miners in solar installation is not an extensive process, Herring said.

Vivint has increased the number of its installation crews by almost 50% in the last five months on the back of strong sales growth in states like California that have supportive legislation for rooftop solar. The company operates in eight of the 25 U.S. coal-producing states, including sun-filled states such as Colorado and Arizona, and sees parallels between the safety and quality standards necessary to coal mining and those requirements found in the solar industry. Vivint provides two to four weeks of technical, on-the-job training to workers without prior knowledge of rooftop solar installation. Sunrun also provides safety and quality training and on average 40 hours of training overall in the first year of employment, according to Herring. For employees that come to Sunrun without prior experience of installing solar panels, the company “provides the required training and certifications needed for them to succeed,” said Herring. Installers and technicians are an “integral part” of Sunrun’s business in states that see big drops in coal mining jobs, such as Maryland, New Mexico and Texas, he added.

Wind

Goldwind’s training program for wind energy technicians in the U.S. demonstrates the fast growth of the sector and the need to retrain technical employees in skills related to a relatively new industry. The company is actively recruiting technicians to work at projects in Texas, Ohio, Illinois, Vermont and Montana and will be offering training on its two-week programs for successful individuals, said Sale.

“When we first began Goldwind Works we anticipated a large influx of applicants of unemployed individuals directly from coal-related companies, but what we came to find was that many other ancillary industries were also impacted by the downturn in the demand for coal,” Sale said in a statement. “We saw applicants ranging from land surveyors and fire fighters, to truck drivers and mechanics, all looking to move into a more stable, growing industry like wind.”

Goldwind plans to expand the program outside the U.S. to Canada and possibly Mexico as turbine contracts are secured, he said.